John Baskerville was a writing master, a carver of gravestones, japanner, type founder, printer, industrialist, Enlightenment figure, free thinker, deist, and the man who designed and created the typographic punches which are at the heart of this project.

Little is known about Baskerville’s childhood or schooling, except that in 1707 he was born in the Worcestershire village of Wolverley. In 1726/8 he moved to Birmingham where he lived for the remainder of his life. Initially he worked as a writing master and a letter carver of gravestones but in 1742 he was granted a patent for japanning and established a manufactory for producing household goods and other useful items. Baskerville’s fashionable japanware was exported to clients across the globe, including Clive of India (1725–74), and its success earned him a fortune. In 1750, his wealth enabled Baskerville to return to his first interest, the creation of letters, when he designed a typeface which made eighteenth-century Birmingham a town without typographic equal and which changing the course of type design. Baskerville not only created one of the world’s most historically important typefaces, but he also experimented with casting and setting type, improved the construction of the printing press, developed a new kind of paper, and refined the quality of printing inks. His typographic experiments put him ahead of his time, had an international impact and did much to enhance the printing and publishing industries of his day.

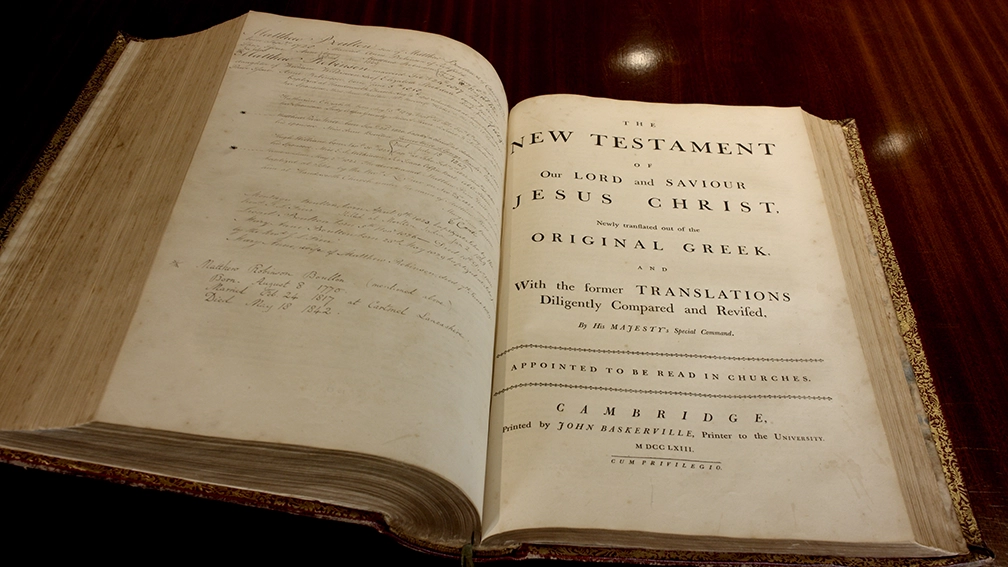

The books Baskerville printed in Birmingham between 1757 and 1774 are recognised by printing historians, librarians, and bibliophiles as masterpieces of the art of book making which, as Thomas Babbington Macaulay wrote, ‘went forth to astonish all the librarians of Europe’. Baskerville commenced by printing an edition of Virgil’s poetry (1757) and continued with authors of the English cannon such as Milton, Addison, Congreve, and Shaftesbury. Whilst Baskerville’s books were well-received in Europe and America, at home he suffered the disapprobation of the British printing and publishing trades which regarded him as an amateur and a provincial who lacked a university education. Such negativity persuaded him to temporarily abandon printing and he passed the use of his typographic material to his foreman, Robert Martin who, between 1767–68, printed five titles including the Works of Shakespeare. Baskerville returned to printing in 1769 when he issued a Bible in parts, and a series of classical volumes including works by Terence, Horace, Ariosto and Lucretius; he concluded his output with William Hunter’s The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus (1774). In 1758 the University of Cambridge elected Baskerville as its printer where he realised his ambition to print an octavo Book of Common Prayer (1760) and a folio Bible (1763). Baskerville’s Cambridge Bible is still regarded as one of the world’s most beautifully printed books. Baskerville died in 1775 and in the same year An Introduction to the Knowledge of Medals appeared ‘Printed by Sarah Baskerville’, the volume was probably started by Baskerville before his death and completed by his widow or Martin.

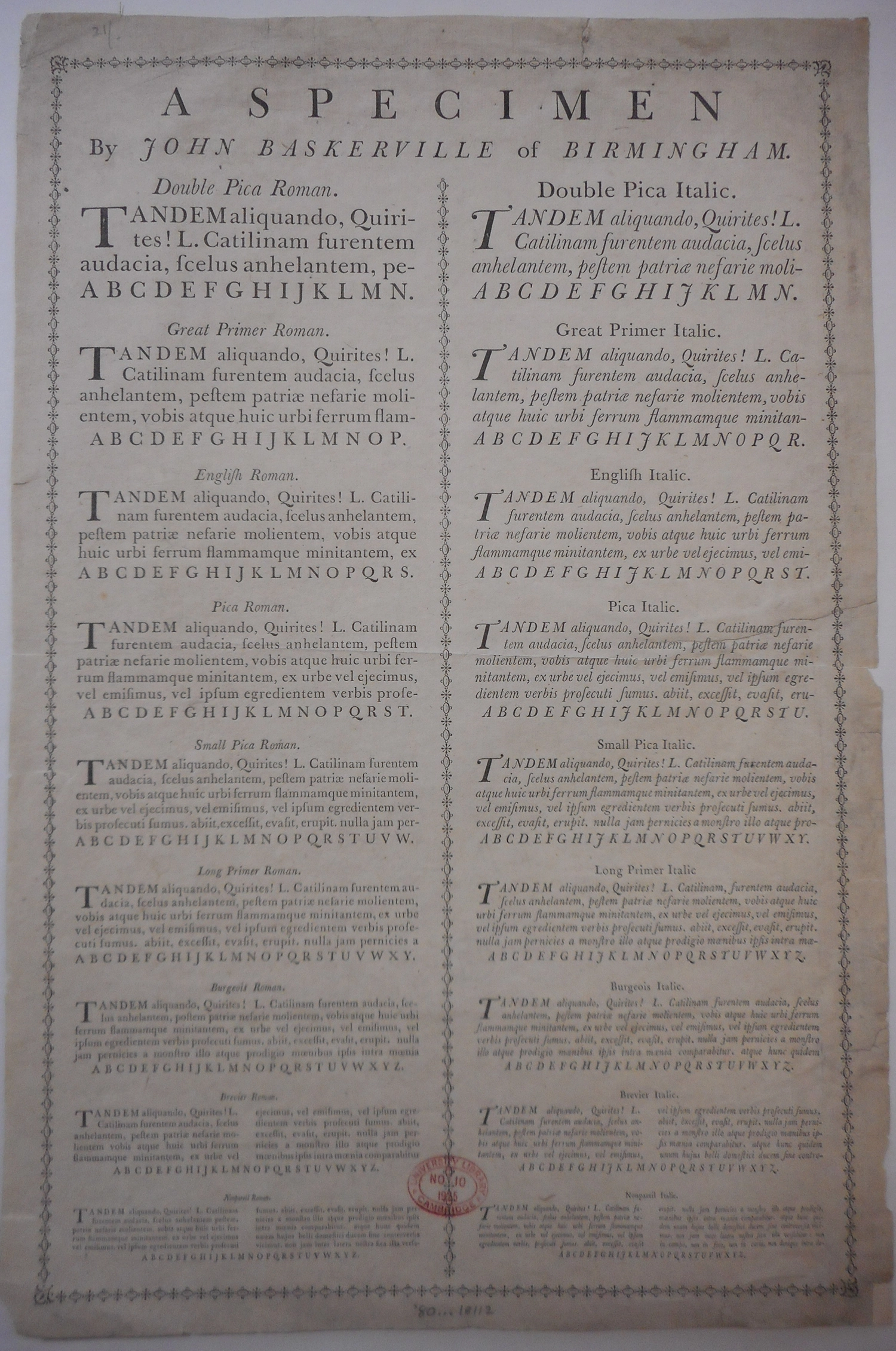

‘Baskerville’, with its well-considered design and elegant proportions its methods of thickening or thinning parts of a letter, and its sharp and horizontal treatment of serifs, is one of the world’s most widely used, enduring and influential typefaces. Admired by Benjamin Franklin in America, Giambattista Bodoni in Italy, and Voltaire in France. Baskerville initially drew his typeface on paper in two-dimensional form. Translating his two-dimensional designs into three-dimensional metal printing type was a three-stage operation. Firstly, his letters were cut in reverse and in relief on short lengths of steel known as punches. High-level metalworking and engraving skills were required to cut punches and accurately reproduce his design. The punch was ‘tempered’ to increase its toughness and enable its use as a tool. Secondly, the punch was hit into the surface of a softer piece of metal, generally copper, leaving an impression of the ‘right-reading’ character to be cast. This was called the matrix. Finally, Baskerville’s type was manufactured when the matrix was passed to the type-caster who inserted it into a mould into which molten type-metal—an amalgam of tin, antimony, and lead—was poured. This produced a cast of the type in relief and in reverse.

When Baskerville died in 1775 his type-founding equipment was sold by his widow, Sarah, to Caron de Beaumarchais (1732–99), diplomat, publisher, and playwright. Beaumarchais greatly admired Baskerville’s types and used them to produce his Kehl editions of the complete works of Voltaire. Subsequently the punches went to Paris where they remained for 150 years during which time the punches changed ownership seven times and their origin was forgotten. In 1917 the punches were owned by the Bertrand type foundry, who cast Baskerville’s founts under the name of Elzevirs ancient and advertised them in its prospectus of that year. The American typographer, Bruce Rogers (1870–1957), however, who, having seen the prospectus, suspected their identity. In November 1936, the Bertrand foundry was bought by Deberny et Peignot type foundry, who acquired Baskerville’s punches. Its director, Charles Peginot (1897–1983), generously offered to return them to Britain and presented them to the University of Cambridge on 12 March 1953 at a ceremony at Emmanuel College in the presence of the French Ambassador, René Massigili. The collection comprises around 2,750 punches, which are now owned by Cambridge University Press & Assessment and are housed in the Historical Printing Room in the University Library.